What is the Noble Eightfold Path?

A Brief Explanation of the Buddha’s Path of Liberation

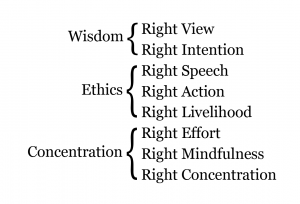

The Eightfold Noble Path is one of the first teachings the Buddha gave, shortly after he attained Enlightenment. It represents the Buddha’s summary of what needs to be done if one wants to also attain liberation from suffering. It is divided into:

Right View

Right Intention

Right Speech

Right Action

Right Livelihood

Right Effort

Right Mindfulness

Right Concentration

However, it is often grouped into ethics, concentration, and wisdom. Like so:

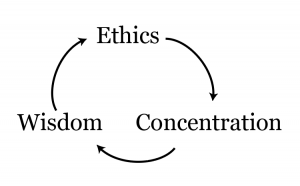

All three of these aspects are considered equally important in the Buddhist path. If our ethical behavior is failing, then we will be full of remorse and agitation, and it will be impossible to settle our minds; and if our minds are not settled, then we won’t be able to see things clearly with wisdom. So the three parts of the path support each other:

Ethical behavior leads to a settled mind, which allows us to see things more clearly, which in turn allows us to discern with more subtlety between skilful and unskilful actions. So it’s not like one part of the path has priority over the others, nor is it the case that one goes “step by step” and after cultivating one aspect we move on to the next. Rather, all aspects of the path mutually complement one another.

Ethical behavior leads to a settled mind, which allows us to see things more clearly, which in turn allows us to discern with more subtlety between skilful and unskilful actions. So it’s not like one part of the path has priority over the others, nor is it the case that one goes “step by step” and after cultivating one aspect we move on to the next. Rather, all aspects of the path mutually complement one another.

With this in mind, let’s briefly unpack each element of the Noble Eightfold Path.

Right View

We all depend on our ideas and preconceptions to navigate the world, and the Buddhist path —at least during the early stages— is no exception.

For example, imagine that one day you are riding a bicycle and suddenly you notice that the road feels unusually bumpy. You stop to check your tires, and sure enough: one of them is flat. So you take out your repair kit and patch it up before inflating the tire and moving along. Problem solved!

Notice that the series of actions required for you to diagnose and fix the bike would have been impossible without an accurate view of the situation. For it to happen, you had to understand that

- the road feeling this “bumpy” is abnormal,

- that this is probably caused by a flat tire,

- that the way to fix a flat tire is by applying a patch, and

- that there are patches in your backpack.

All of these are views, i.e., mental structures that lead you to interpret the situation in a certain way. In this case, these are right views because they correspond to reality and lead to improving the situation. A wrong view might be, for example: “It’s normal for the road to feel bumpy,” or “The bicycle is broken and I need to get a new one!”

This is a silly example, but it has an analogue in the path outlined by the Buddha. For us to even begin to take interest in this path, we first need to have an accurate reading (view) of the situation. Namely, we need to understand that

- a) our human existential situation is problematic,

- b) that this less-than-ideal state of affairs has concrete causes,

- c) that these can be addressed, and

- d) that our problematic existential situation can be resolved.

If we don’t see things in this way, why would we even bother to embark on the Buddhist path? For example, if we believe (as many modern philosophers do) that there’s something irredeemably hopeless about the human condition, then there would be no reason for us to try to find a way to fundamentally improve it.

Right Intention

Right Intention serves as the complement to Right View. Understanding that there’s suffering and that it can be stopped is a big step, but it’s not enough to lead us to take action. To continue with the previous example: we might understand that there’s a problem with our bike tire, and that it could be fixed, but we might just be too lazy to do anything about it, so we just keep riding our bike (until it finally breaks down for good!)

So two things are needed to improve our situation: the right evaluation of the problem, and the actual determination to do something about it. The latter is Right Intention. Without Right View, we might want to do something about our problems, but we won’t know where to begin; without Right Intention, we might understand our existential predicament, but still not take any action to improve our situation.

In the context of the Buddhist path, Right Intention refers specifically to mustering the determination to stop planting the causes for suffering, and start planting the causes for non-suffering. This means to abandon greed, aversion and delusion, and cultivate non-greed, non-aversion, and non-delusion.

If this sounds too abstract, keep reading. The next steps of the path will help clarify what this means in practice.

Right Speech

As you might have surmised, unlike a bicycle tire, the mind is subtle, complex and multilayered, so in reality things are not so simple as in our example.

For example: both having a momentary dislike of my co-worker and physically attacking them are examples of aversion, but clearly there is a big difference in degree. The point here is that we need to get the coarsest mind activities (those responsible for how we speak and act) under control before we move on to tackle the subtler levels of thinking and intending. This is where ethical behavior comes in, the first category of which is Right Speech.

Right Speech is defined as refraining from talking in a way that harms others, so things like

- telling lies,

- speaking harshly or abusively, or

- speaking frivolously in a way that wastes people’s time and energy.

When we make a determination to not speak in these ways, we begin to actually walk the path in our daily lives, because we are taking practical steps to reduce the coarse forms of greed, aversion and delusion in our behavior, which are the causes of suffering. In other words (and to simplify greatly), we had the Right View regarding our situation; we mustered the Right Intention to act on it; and this intention is showing in our actual efforts to practice Right Speech and the other ethical components of the Eightfold Path.

Right Action

As with Right Speech, the point here is that we want to regulate our behavior to avoid planting the causes of suffering. Specifically, the Buddha spoke of the following behaviors as those that should be avoided, for they are the most problematic of all:

- killing other living beings,

- stealing from others (taking what is not given),

- committing sexual misconduct, and

- consuming intoxicants that dull or confuse the mind.

“Killing living beings” refers to beings with conscious awareness, so basically human beings and animals (not plants or mushrooms). “Sexual misconduct” is defined as avoiding blatantly harmful acts, like cheating on our partner or using our sexuality in an abusive way, as well as having sex outside of a committed relationship (or marriage).

Right Livelihood

This is the final component in the ethical part of the Eightfold Noble Path. It refers to not engaging in occupations that bring harms to others, or lead them to break the precepts, such as

- selling weapons,

- selling intoxicants, or

- working as a butcher, fisherman or soldier.

Right Effort

As we have been saying, training to abandon the sources of suffering involves regulating first the “coarse” aspects of speech and behavior, before gradually moving into the subtler domain of mental activity. For this, we rely on the next section in the Noble Eightfold Path which deals with concentration, or mental stability.

The first component is Right Effort. In this context, Right Effort is directed towards four goals:

- Preventing not-yet-arisen unwholesome mental states,

- Abandoning unwholesome mental states already arisen,

- Generating not-yet-arisen wholesome mental states, and

- Nurturing wholesome mental states already arisen.

‘Unwholesome’ refers to greed, aversion and delusion, and ‘wholesome’ to their absence. In cultivating Right Effort, we adopt an attitude of vigilance towards our own mind: whenever we find that we are in the grips of desire or hatred, we make a conscious effort to move away from this, while also putting energy towards developing joy, peace and contentment.

Because we have a tendency to operate in auto-pilot during everyday life, it is very important to develop a consistent meditation practice as the ground of Right Effort. Otherwise, we are always one step too late when it comes to dealing with the mind.

Right Mindfulness

There’s a passage in the Dhammapada, an important collection of the Buddha’s sayings, which states that “those who are mindful do not die; those who are mindless are as if dead already”. This points to how important mindfulness is in the Buddhist path.

Mindfulness is perhaps the aspect of the Eightfold Path that has been most influential in popular depictions of Buddhism in the West. Certainly, it is one of the most distinctive aspects of Buddhist meditative training and it is a central component in the path.

However, it is also important to emphasize that the Buddha didn’t just teach mindfulness (as the rest of this article shows). Mindfulness without the other components of the path, such as Right View or Right Action will not lead towards the end of suffering. The Eightfold Path is a holistic system that encourages us to develop all parts of our personality, and we ignore this at our peril.

The Buddha defined Right Mindfulness in terms of four different areas of experience:

- The Body,

- Feelings (i.e., whether things feel pleasant, unpleasant or neutral),

- Mental states, and

- Mental factors.

Right Concentration

Right Concentration refers to the one-pointedness of mind (samadhi) that comes as a result of meditative practice. The experience of samadhi is associated with very pleasant mental feelings and it allows the mind to settle and stabilize. At a very advanced level, it can lead into one of the deep states of meditation, or jhanas, deeply peaceful and blissful states.

Samadhi is an important component of the Eightfold Path in its own right, but also because the stability it provides feeds into the other aspects. For example, when our minds are calm and collected, we will be more likely to speak in a reasoned manner (Right Speech), to see clearly and counteract unwholesome mental states (Right Effort), or to gain confidence that this path of practice leads to joy and away from suffering (Right View).

Conclusion

As we have seen, the Eightfold Noble Path is a comprehensive and holistic system for developing every aspect of our lives in which each aspect contributes to the development of all the others.

It begins with an accurate assessment of our situation (Right View) and a determination to act accordingly (Right Intention). This leads to the very practical question of how to speak (Right Speech), act (Right Action) and live (Right Livelihood) in a way that decreases suffering for ourselves and others. It then moves on to the mental aspects that we should cultivate to further address the problem of suffering: cultivating wholesome mental states (Right Effort), maintaining presence of mind throughout our lives (Right Mindfulness), and developing a clear, still mind (Right Concentration).

If we remain heedful of these various components, we will then have a framework for training ourselves slowly but surely in the direction of less suffering and more joy, happiness and peace.