What Are We Reading At DRBU? Yoga Sutra of Patanjali and the Bhagavad Gita

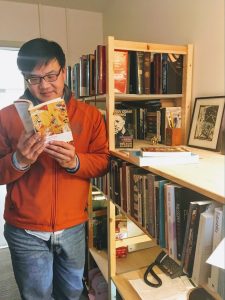

The following is a brief recommendation from Professor Franklyn Wu, instructor for the Indian Classics I course in the B.A. program this fall.

Actually, I would like to recommend two books to be read in sequence: the Yoga Sutra of Patanjali and the Bhagavad Gita. The Yoga Sutra gives a succinct summary of the philosophy and spiritual teaching underlying the yogin practices that have been undertaken for millennia. According to the Yoga Sutra, prior to working on posture, breath, and sense withdrawal, all of which lead to further work on focus and mental absorption (these are the latter limbs of the eight limbs of yoga), a yogin practitioner has to first work on the first two limbs–yamas (ethical code) and niyamas (observances)–as necessary preparation.

First among yamas is ahimsa, or non-harming. This virtue is very much part of the zeitgeist of the modern yoga movement and was a core personal and political principle upheld by Mahatma Gandhi throughout the resistance movement he led against British rule. In light of ahimsa’s prominence, reading the Bhagavad Gita was a jarring yet rewarding experience for the students and me!

Any student of a philosophical, mystical, or spiritual teaching would relish an opportunity to see how such teaching is applied. Somewhat akin to its Platonic counterparts, the dialogue between the great warrior prince, Arjuna, and his charioteer, Krishna, (who is also the incarnation of the yogin spiritual ideals and the all-powerful creator god) serves to illuminate the teaching that one can find in the Yoga Sutra and other texts for the purpose of helping Arjuna figure out how to act. The experience is jarring because the dialogue takes place on a battlefield and Arjuna must decide whether to fight and kill his uncles, cousins, and teachers. Further, Krishna instructs Arjuna that fulfilling his duty as a warrior and slaying his family is the path to the yogin ideal, albeit with a significant caveat that one needs to carry out the action while completely renouncing the results (rewards or punishments) of that action.

In this way, the Gita, considered one of the most spiritual Indian texts, stirs emotions and begs just as many questions, such as: What are our duties and where do they come from (or who decides what they are)? If our duties are predestined, is there space for personal agency? How do we reconcile the Gita with the core teaching of ahimsa (non-harming)?

Gandhi was a well known student of the Gita and his reflections on the text eventually became a book. Within it, he wrote, “Let it be granted, that according to the letter of the Gita it is possible to say that warfare is consistent with renunciation of fruit. But after forty years’ unremitting endeavor fully to enforce the teaching of the Gita in my own life, I have in all humility felt that perfect renunciation is impossible without perfect observance of ahimsa in every shape and form.”

So why use warfare as the context for spiritual teaching?