The Practice of Weaving: Tapestries by Stephanie Hoppe

Presented by the Dharma Realm Buddhist University Arts Initiative

My journey to California this past fall brought me the opportunity to view The Practice of Weaving: Tapestries by Stephanie Hoppe. Composed of 24 tapestries and rugs spanning several years of Hoppe’s career, the exhibition was hung throughout the first floor of the Dharma Realm Buddhist University Building in Ukiah, California. Arranged on the walls next to classrooms, I could not help but see the alignment between the teachings of the University and the expression of Stephanie’s practice. This extensive look at the work of two decades highlighted Hoppe’s technique of four selvedge handwoven tapestry and Navajo twill tapestry, and her use of hand-dyed, handspun yarns. Hoppe’s style of abstraction is grounded in nature and emphasizes the meditative nature of weaving. She also collaborates with other artists from time to time, as the show includes some weavings that were designed by Bernice Bing, a Northern California painter of Chinese descent.

The University is located in Talmage, just outside of Ukiah, and is a place for Buddhist education for children in elementary and high school, as well as adult study. There is a temple of Ten Thousand Buddhas on the grounds, filled with small and large statues of the Buddha and bodhisattvas, many carved by Master Hua, the founder of the University. Stephanie refers to an extension course she attended that caused her to understand her fascination with weaving as similar to the “psychological mechanisms through which our consciousness arises and operates. The meticulously detailed step-by-step explication exerted on me [Stephanie] the same fascination that weaving does, where I proceed row by row with wool and silk yarns to fill in the empty spaces of the warp and build up a finished piece.”

The first grouping of tapestries in the exhibition is titled Consciousness Only. It includes three panels, 1 Light, 11 Insight, and 111 Meditation. Says Hoppe, “The weaving took quite a while, [December 2019 to April 2022], affording many hours of meditation on both weaving and consciousness, as well as a welcome refuge during the pandemic.” This trio of tapestries makes very effective use of pattern, using triangle shapes in repeats and chevrons to hold the place for more organic elements. The use of eccentric weave seems to be one of Hoppe’s favorite techniques. The flowing lines of the eccentric weaving offer energetic passages as well as softer moments, much like our active and dream-like brain waves.

The Fire at the Heart of Winter is a tapestry that immediately brought to mind for me the hexagrams of the I Ching (Yi Jing), with groupings of lines that represent elements of nature or the cosmos, such as The Creative, Enthusiasm, and The Cauldron. Stephanie has drawn parallels between striped Navajo Chief’s blankets and the patterns of the I Ching, further exploring her interest in culture and nature.

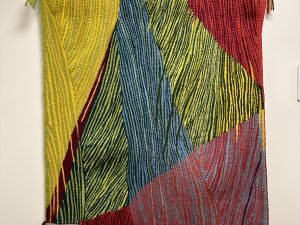

Triangulations uses a palette of strong primary and secondary colors and has a thick, spongey weft and a sculptural wave in the body of the tapestry that allowed me to relax despite the energizing effect of the colors. Several of the tapestries gave me this permission and I found it very refreshing. “Unlike painting or drawing,” says Hoppe, “where we add images to an existing background, weaving involves creating figure and ground simultaneously, sometimes arresting any distinction between the two.”

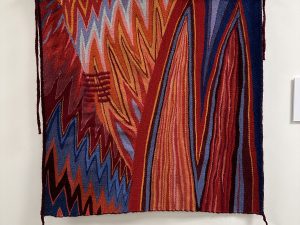

Returning to the wisdom of the I Ching, the next tapestry is an energetic and brightly flame- colored tapestry that presents the inner and outer experience of wildfire. This beautiful tapestry, Wild Fire, is large, weighty, and has sculptural waves that seem to increase its gravitas. It is embellished with Hexagram 56, called the Wanderer, or sometimes The Stranger, and offers the image of the sweeping destruction of wildfire, or the havoc wreaked on a community by a stranger. The hexagram is embroidered onto the surface of the tapestry, while the wedges of color energize and warn us to run! “The mountain endures, it cannot burn; fire flashes across it and departs, transient, consuming whatever it encounters and then, itself.”

A grouping of tapestries that refer to Hoppe’s gardening during drought times follow. The first of these, Iris Endures, began the series by showing up in Stephanie’s yard as “small clumps of iris that flourished with or without watering, though only where they chose…” A useful as well as beautiful plant, Native Americans used the fibers from the long leaves for nets and snares. The long curve of the leaves inspired Hoppe to “weave a series of tapestries, using the same design of long, curving leaves and two blossoms, in a variety of weaving techniques.” The exploration of one design executed in a variety of weaves and approaches is an interesting exercise. Each one has integrity and individuality.

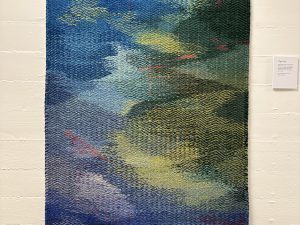

One of my favorites of Stephanie’s designs is a tapestry called Autumn Reflected in the Eel River. There is a peace that comes from observation and reflection, and she has tapped into that sensation. The subject of leaves on trees reflected on the water has been explored beautifully here, in abstraction. The rich colors of the ground buoy up and showcase the small bright leaves and curves of color give the feeling of floating on the water’s surface. Says Hoppe, “this is what I saw on a November afternoon, kayaking on the Eel River: a deep, still pool shaded from the low sun by the hillside to the south, dark blue-green water shimmering with rectangular shards of the reflected bright colors of sunlit trees on the opposite shore and the clear blue sky – Nature pixelated and ready for the loom.”

Hoppe has experimented with stitching over the surface of some of her tapestries. Red by Red on Red is just such a tapestry. “Is it possible for there to be too much red?” The embellished tapestry achieves a wind-blown, cosmic effect – very active!

Another stitched and reworked tapestry is Ancient Rites, which almost looked felted to me. The waves in the body of the tapestry are quite attractive. Stephanie over painted the tapestry with yellow and gold dyes, and over stitched in colors of red, ochre, yellow green. The stitching offers a strong sense of narrative, like sign language, cave markings, or rock paintings. An ancient map, if you will.

I find Onset of Winter; Some Birds, No Rain to be one of the loveliest of all the tapestries in the show. Using eccentric weft weaving, soft blues and wheat-gold, Hoppe creates a sense of murmuration and dryness, a longing for water, and the pleasures of long fall days in California.

I hope that some of you will have a chance to see some of these lush and beautiful weavings. While the exhibit at the Buddhist University has been taken down, I understand some of them are on display now, along with tapestries by Ellen Athens, at Pacific Textile Arts (PTA) in Fort Bragg, Mendocino County, California. They will be at PTA for the month of February.

Tapestry Weavers of Pacific Textile Arts 450 Alger St., Fort Bragg, CA