What’s your overall feeling of studying and living here at DRBU?

Overall, I came in not knowing what to expect. And I feel like in many ways, I am definitely pushing my comfort zone, adapting to new situations and new environments. But in the same way, I’m really grateful that I’m doing that in an environment that’s so respectful of everyone’s differences, including mine. And so that makes me feel safe. Everyone’s just been really supportive. So I just take it one day at a time; every day is a bit different.

Could you say more about stretching your comfort zone?

Could you say more about stretching your comfort zone?

It’s just [that] monastery life is very simple. And it’s much more regimented. It’s something that I’ve been so accustomed to. It’s challenging but in a different way. And here, like I said, I don’t know what to expect when I go to class. Especially with these texts that we’re reading, which are so thought-provoking and inspiring that you don’t know what direction we might take that day. So I am learning to think about the texts in ways that I never would have thought of before, especially with the Buddhist texts. The way I have been brought up, I just read them as they are. I never would have raised the questions or doubts and concerns that people bring up in shared inquiry. It’s a challenge to learn a new way of learning. But at the same time, it is so valuable because it is something I can’t experience anywhere else. I would never have thought of some of the issues that people raise. And that’s so important for someone like me who wants to be able to share the Dharma with the Western world. It’s so important to know where people are coming from and how people will potentially approach the text in order for me to actually be effective, be relatable to people, instead of just thinking of it from my own perspective, which is much more narrow. So every day, I’m becoming more open-minded. It’s challenging, but it’s also very rewarding.

That’s beautiful. We can go further on this topic. But before that, could you describe a typical day in your monastery in Canada?

In Canada, it’s pretty simple. It’s actually pretty similar to what I have heard about the schedule at City of Ten Thousand Buddhas (CTTB). So we wake up at 3:30, go to the morning service from 4 to 5:30, or on special days, it will be, maybe, 6:30 on certain Buddhist commemorative days. And then we have a morning meal. And then there’s some kind of Dharma talk, either by the residents or we listen to a recording. And then there’s the morning work period. Everyone’s assigned to take care of a certain area of the temple. At 8 o’clock, we recite sutras. And that’s usually until about 9. And then we continue our assigned work until about 10:45. Then we have the lunch service, and that’s followed by another Dharma talk, usually a recording. And then we have a rest period, when you can do what you like; many people engage in their own study or practice. And then we have the afternoon work period. That usually goes to about 5 or so, depending on what your conditions are that day and what work you’re assigned to. From 5 to 6:30 is another rest period, usually for showers, laundry, more self-practice, etc. And then our evening service is from 6:30 to 9:30. And then basically we get ready for bed and go to sleep at 10. And that’s our day. Then start all over again. So it’s pretty simple.

Is there anything in your temple life in Canada that you miss because you don’t have it here?

I definitely miss having group practice sessions in the Buddha Hall. Just the collective energy of everyone coming together and participating in ceremonies together. But because of the pandemic, it’s not possible.

Is there a class that’s particularly challenging? Or are you struggling with anything?

I struggle with a lot of things. [laugh] Reading the Western philosophical texts is probably more challenging for me because I’ve never read the work of these amazing thinkers. Some of them are not easy to read, but I find that it’s definitely worth putting the effort into it. Because like I said, I hope to be able to share the Dharma with the Western world, and so I need to understand Western ways of thinking. And I’m always really interested to see how there are many areas that overlap with Buddhist ideas. That always interests me.

Could you say more about the overlapping of Western thinking and Buddhist ideas?

I’ll read something, and I think, “wow, this sounds very familiar!” I’m trying to think of an example. [pause] I don’t think I can come up with an example off the top of my head. It just makes me feel that it’s hard to call Buddhism a religion because the so-called Buddhist teachings are so universal. Anybody can relate to them. You don’t have to be religious to share the same ideas.

But what makes Buddhism different, though? Is there anything that you see Buddhism is different from Western thinking or other religions?

I think what makes Buddhism different is that it’s really only concerned with how to reduce our suffering. And it points to the source of our suffering being craving and desire. In other Western texts, there are other points of consideration, whereas in Buddhism, we are mainly concerned with people’s suffering and what to do about that. Through our practice, if we can gradually reduce those desires, we can increase our freedom from the grasp that those desires have on us. And with that increase in freedom, there’s less suffering. I think that’s what makes Buddhism different. We’re just concerned with what to do about human suffering. When I do something, is it going to cause more suffering? Is it going to cause less suffering? That’s our main concern.

What do you think about the difference in the definition of suffering between Buddhism and other teachings?

I think one difference would be that the common notion of suffering is not having the freedom to fulfill your desires, whereas in Buddhism, you restrain yourself from those temptations to satisfy all your desires. You restrain yourself from indulging in fulfilling all your desires. By doing so, the result is that you have freedom from those desires.

So what brought you to Buddhism initially?

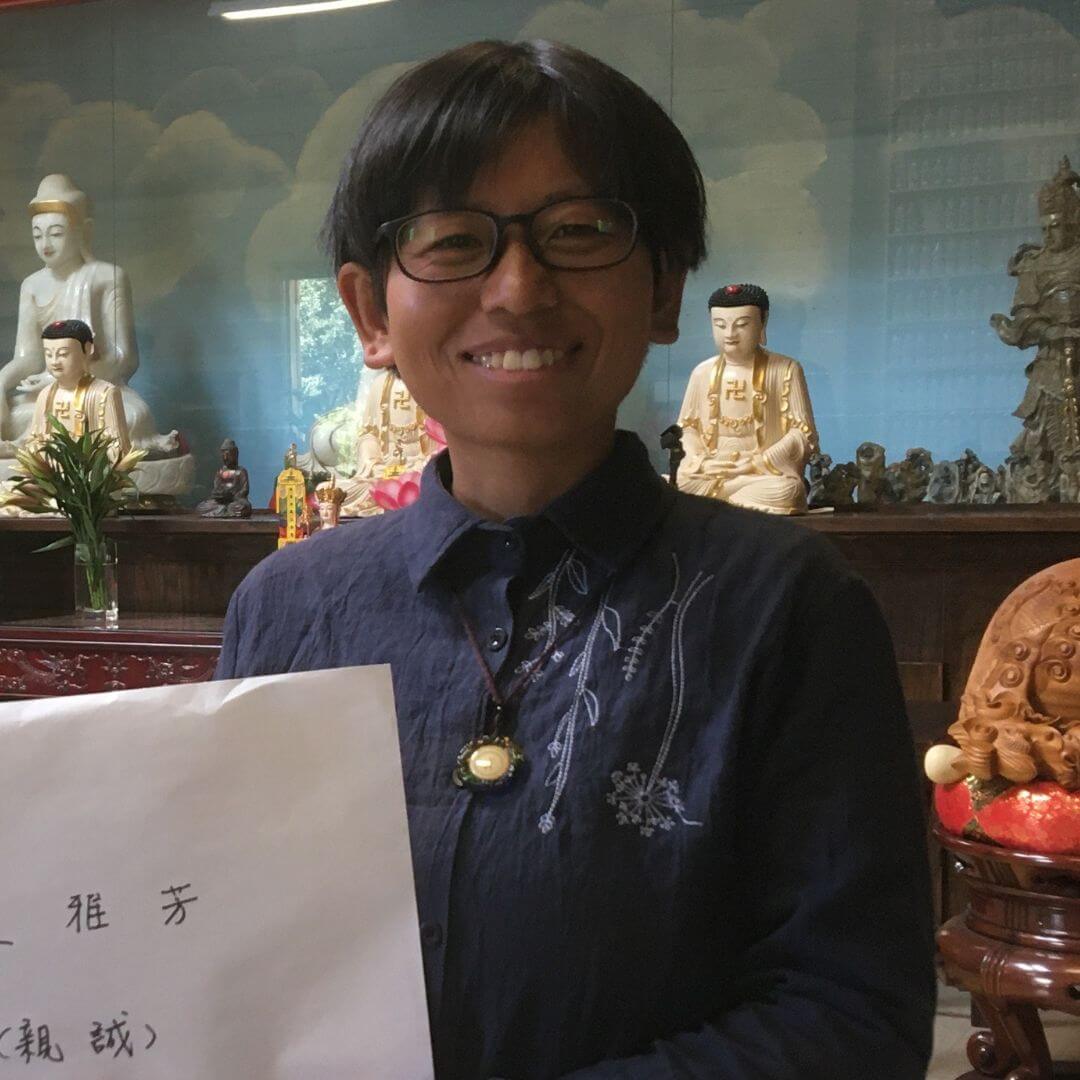

I was just born into a Buddhist family. I went to Buddhist temples and attended lectures with my mom as a young child. And I was part of my temple’s youth program. When I graduated from that, I served as a volunteer for a long time.

Some Buddhist children resist Buddhism, and you were completely drawn to it.

That’s true. Like, my brother and sister are definitely not Buddhists.

There must be something in the temple that drew you in and led you all the way to becoming a monastic. What is that?

It’s hard to put into words, but I would have to call it a sense of homecoming. It always felt like the temple was my second home. And when the conditions arose that I had the opportunity to stay there as a resident, I almost felt a sense of calling: That was where I belong.

What brought you to DRBU, and how did you hear about CTTB?

I’m involved in a lot of the translation work that we do at the temple (Ling Yen Mountain Temple Canada). And we refer to a lot of Buddhist Text Translation Society (BTTS) translations as references. So I guess I’ve always known about this place. What brought me here was this intention to learn more about how to connect the Chinese Buddhist tradition with the Western world. That’s something that I feel we do very well here at CTTB. And I thought coming to DRBU would be the perfect way to do that. Basically I want to make the best use of the form and conditions that I’m in, being both Canadian and Chinese. I feel like I can use that to share the Dharma with the Western world, live the teachings, and share the teachings.

Do you have a preferred form of sharing the teaching?

I don’t really have a fixed idea in my mind. I think the Dharma can be shared in so many ways. I don’t necessarily need to make a speech or write a book or something. I feel that just in everyday interactions with people who come by the monastery, who either have affinity with or don’t have affinity with you, we can create affinities for people to want to practice. Some people can be inspired just by seeing our practice. You don’t even have to say anything. But in addition to that, I would definitely like to make the best use of my conditions and contribute to the translation of the teachings from Chinese to English. Hopefully, I can make them more accessible to Westerners.

Every morning when you get up at 3:30, what is it that pulls you out of bed?

Good question. I think of early morning as this golden opportunity to capture the time when the mind hasn’t started thinking about all kinds of things. [laugh] My best ideas come to me in the morning. It’s the calmest, the quietest, both inside and out. Whether I participate in the morning ceremony, or I do my own practice or recitation, it all helps me to set my intention for the day.

Before going to bed, how do you normally feel at the end of the day?

Recently, I feel like I have a lot of unfinished work. [laugh] But that’s okay. Regardless, I still try to just settle down and reflect and be grateful for whatever went on in the day.

I go to bed full of gratitude, gratitude for another day I’ve been given to practice. There’s no guarantee that I will wake up the next day. And before I go to bed, I usually say a short prayer.

What is your experience in doing dishwashing in the CTTB kitchen?

It always feels great to be of service. It’s another way to express my gratitude for all the hard work that goes into making our meals. Also expressing gratitude, not just toward others, but gratitude for the fact that I still have a healthy body, arms, and legs. I want to use them to serve others. And this is just a very small way that I can do that.

In terms of studying at DRBU, do you have a favorite class?

[pause]

Maybe it’s not a good question. It’s like asking who your favorite parent is.

[laugh] Honestly, I don’t think I have a favorite class. Because like I said, every day, every class is different. You never know what to expect. To have a favorite class would assume that this class is always like this. But it isn’t.

What has changed in you that stands out in your first semester here?

I think I’ll never read Buddhist texts the same way. Just being able to hear so many different perspectives really opened my mind to how different people can look at the same text. I will definitely not read the texts the same way.

Is there anything that you want to do but haven’t been able to do here?

Something really practical. I want to visit the Buddha Hall. I want to actually take a look at the boys and girls schools. Those are things that I was really looking forward to [but couldn’t do because of the pandemic]. I’ll keep praying for another year and a half. I am hopeful.

Is there anything that you want to say but I haven’t asked?

To express how much I admire and respect the instructors here. I think they’re all really amazing people. They know the texts so well that they can go into a class, and regardless of what direction is taken, they’re able to bring us back to the primary text. I think that’s really wonderful. I hope to have that level of familiarity with the texts as well.

What gives you the most joy?

The feeling that I get when something that I’ve said or done has a positive effect on others.