Buddhist Classics

Bachelor of Arts in Liberal Arts

On the eve of his passing, the Buddha instructed his students to take as their next “teacher” not an individual, but “the teachings”—the philosophy and practices leading to self-knowledge and a clear understanding of the nature of reality. This vast body of knowledge, initially passed along in an oral tradition, gradually coalesced into a collection of works known as the Dharma and Vinaya—the Buddhist classics.

The use of the two terms Dharma and Vinaya rather than the single term philosophy highlights the central defining feature of these works: the dynamic fusion of theory and praxis. Because the “study of” and “doing of” philosophy mutually respond, the Buddhist classics were not intended merely as abstract doctrinal expositions of readymade knowledge. Rather, they were meant to both inform and form, to explain and engage. Overall, they aim to stimulate a dialogue with oneself that encompasses the intellect, imagination, sensibility, and will; together this dialogue is known as “self-cultivation.

The Buddha once compared these teachings in self-cultivation to a vast ocean: “Just as the great ocean has one taste, the taste of salt, so also this Dharma and Vinaya has one taste, the taste of liberation.” The texts thus pose questions rather than dictate answers. How does each individual construct a world of meaning, and how can that world be transformed and deepened into a site of liberation? The freeing up and broadening of the human spirit to pursue such questions was the original intent of the Buddhist classics and the continuing purpose for studying them now.

The texts come embedded with a systematic and critical discipline of inquiry—one characterized by rigorous probing, radical questioning, and careful analysis of both the subject and object of study. This integration of the personal and philosophical seeks to harness knowledge with virtue and to guide action with insight.

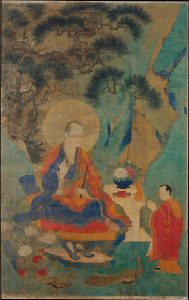

In the Buddhist Classics strand, the emphasis is placed on studying Buddhism not merely as a historical event, but as a living philosophy and embodied discipline. Students learn about, from, and through the texts. This “laboratory” approach allows students to test theoretical soundness with an experiential index and to appreciate the Buddhist way from a vantage point within, rather than at a sterile remove from that tradition.

The freshman year readings focus on the philosophical and particular phenomenological origins of the Buddha’s teachings. Despite their antiquity, these teachings seem to retain a lively relevance in modern times and across cultures. Students consider and explore the existential concerns and conditions that prompted the Buddha’s own spiritual journey. The first year’s themes thus center on basic questions and issues concerning the individual living the examined life: identity, belonging, and alienation; the quest for knowledge and certainty in a contingent universe; doubt, meaning, and purpose; mortality and its implications; conditioned existence; inspirations for and alternatives to the spiritual path; and liberation, self-determination, and potentials for freedom. The year begins with the study of sacred texts from the Pāli canon, including selections from the five Nikāyas, and transitions into Mahāyāna texts such as the Sixth Patriarch Sūtra, the Vimalakīrti Sūtra, and The Sutra in Forty-two Sections.

In the sophomore year, the readings shift students’ field of inquiry from the personal to the social. They move from the solitary individual dimension to probe into those larger patterns, shared structures, and determining factors that shape the more universal human condition. The texts highlight recurring patterns and universal elements that appear common to all humanity and that in large measure frame our lives. The core themes and topics transition from the personal existential questions to the Buddha’s description of deeply ingrained tendencies common to all living beings, habituation, the range and variety of paths of existence along this continuum, the primacy of the “mind” and intentionality, the mechanism of causality that underlies all phenomena, nonduality and its implications, and the ideas of innate potential or inherent capacity for wisdom and compassion shared by all living beings.

Key texts include the Lotus Sūtra, the Longer Sukhāvatīvyūha Sūtra (Infinite Life Sūtra), selected passages from the Avataṃsaka Sūtra, the Essay on the Resolve for Bodhi, the Heart Sūtra, the Vajra Sūtra, the Shastra on the Door to Understanding a Hundred Dharmas, and Ārya Nāgārjuna’s Letter to a Friend.

In the junior year, students address the pragmatic and applied aspects woven in and throughout the texts. The focus turns from the descriptive to the prescriptive to examine the methods— moral, intellectual, aesthetic, contemplative, and behavioral—outlined in the texts for “doing philosophy” in the Buddhist tradition. Students explore the particular ways in which theory and praxis interact to allow for a more direct and total learning experience. Buddhist texts were designed and used both to convey knowledge and guide practice. As such they can serve as laboratory guides for deepening understanding and appreciation of the material. This laboratory approach activates and engages the key modes of learning—cognitive, experiential, abstract, kinesthetic—into an integrated experience. Students are invited to investigate the nature of compassion, its role in spiritual practice, and its connection with insight, and the role of precepts and spiritual practice.

Readings include the Śūraṅgama Sūtra, biographies and autobiographies of eminent Buddhist practitioners, Awakening of Faith in the Mahāyāna, and Nāgārjuna’s Bodhisaṃbhāra Śāstra (The Treatise on the Provisions for Enlightenment).

The themes of the final year explore the pinnacle, or more comprehensive and inclusive philosophy, of Buddhism: the dynamic and complex interconnectivity and interdependence of noumena and phenomena. Students read texts that describe the overarching “oneness” of the nature of reality (the Dharma-realm) as well as the mentality and methods to “enter” or comprehend it. Central to this broad embrace is the paradigmatic Bodhisattva ideal—an individual who is engaged in the world but not of the world, who liberates him- or herself while liberating others, and whose defining qualities are compassion, kindness, joy, and equanimity.

Students are encouraged to consider their education not as an end, but as the first step of a lifelong journey of learning, critical inquiry, cultivation of their character and mind, and service to society. This returns to and highlights the institution’s vision: a liberal education is learning that integrates all aspects of life. It is characterized by a continuous sense of wonder; an ability to weigh, reflect, and wisely act even when faced with ambiguity; and a spirit that looks forward to a life of limitless possibilities.

The focal texts of the fourth year are the Avataṃsaka Sūtra and the Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra. The scope and aim of both is expansive and holistic. They stress an engaged liberation that sees a good life as the total interpenetration of learning and action, self with others, and the human and natural worlds.