Chinese Classics

Bachelor of Arts in Liberal Arts

The Chinese Classics strand focuses on giving students a personal encounter with seminal Chinese thinkers using primary texts as sources of inquiry and insight. As one of the oldest civilizations in the world, China’s longstanding tradition of classical literature confronts issues of universal human concern:

What is the ideal of a good person? What does it mean to live a good life? What are the virtues? How can we achieve personal transformation? How should we relate to other people as well as to the natural world? How should we face death?

Through careful study of classic texts, students become familiar with a range of Chinese answers to these pressing questions. Students will familiarize themselves with concepts such as the Dao, the Sage, the Exemplary Person (junzi), methods of self-cultivation, the significance of ritual, and other important ideas through which Chinese thinkers have framed and debated the most basic of human questions. Through the process of close reading, students develop the ability to take on different perspectives and to recommend, adjust, alter, and even abandon a previous position or stance.

This strand invites students to explore China’s formative thinkers and dominant modes of thought through the exploration of significant philosophical, literary, and aesthetic works. Students will be introduced to a wide repertoire of literary genres as they progress through the strand: poetry, essays, philosophical works, historical writing, hagiography, short stories, novels, as well as ritual and divinatory texts. Through reading these foundational texts, students witness the development of Chinese thought over time and experience firsthand the dialogues and debates between different texts and thinkers.

In a tradition where classics were so deeply revered that entry into the literati class required mastery of and extensive examinations on a classical canon, the development and exchange of ideas in China invariably built upon mastery of foundational classical texts. Furthermore, familiarity with the Chinese context is aimed at deepening students’ understanding of the evolution of Buddhism as it traveled from India to China, where it both profoundly influenced and was in turn deeply transformed by native Chinese thought.

Through deep investigation of a diverse range of Chinese classics, students develop their ability to read, write, and think clearly.

The Chinese Classics strand is crucial to DRBU’s mission, which is to equip students with the necessary skills for understanding and coping with life in our increasingly globalized and multi-cultural world. The complex understanding that comes from the investigation of the central philosophical, literary, and aesthetic works of China provides students with an increased range of resources with which to address pressing questions in their own lives. Furthermore, by devoting significant attention to a non-Western culture, students gain the ability to appreciate a diversity of worldviews and understand the challenges—as well as the necessity—of being able to communicate and translate between different languages and cultures.

Through grounding students in an understanding of the seminal texts of China, the Chinese Classics strand provides students with fundamental skills for active participation as global citizens.

This first year of the Chinese Classics strand is devoted to a study of the classic texts of early China. Students begin their investigation of Chinese thought through a close reading of the Analects of Confucius, taking a brief look at one of his adversaries, the philosopher Mozi, and then moving on to the writings of Mencius, Confucius’ most famous student. Next, students delve deeply into two Daoist classics, the Daodejing, a text in verse form that has been translated into as many languages as the Bible, and the Zhuangzi, a collection of stories and essays by China’s famous Daoist sage. Students then return to the Confucian debate through an investigation of the Xunzi, which expands on Confucius’s ideas but in ways significantly different from Mencius. Finally, students explore the social and political theories of the last major thinker of the pre-Qin period, Hanfeizi.

Interspersed among the philosophical readings above, selections from the Five Classics will also be analyzed and discussed. These include the Shijing (Odes), the earliest collection of poetry in China; the Shujing (Documents), and the Chunqiu (Spring and Autumn Annals), two early historical works; the three Rites Canons, consisting of the Yili (Ceremonials), the Zhouli (Zhou Rites), and the Liji (Rites Records); as well as the Yijing (The Changes), a significant divinatory text. As some of the Bachelor of Arts in Liberal Arts 23 earliest Chinese writings, the Five Classics are truly foundational in the sense that they are the building blocks upon which later intellectual and literary writings are based. An understanding of these texts is crucial to comprehending almost all later Chinese thought.

The third semester of the Chinese Classics strand focuses on significant works of literature, philosophy, and religion from the Han through Ming dynasties. Building on their understanding of early Chinese classics, students can see how the arrival of Buddhism begins to influence the development of Chinese worldviews and practices. The year opens with an examination of the Han dynasty syncretic work, the Huainanzi, which takes elements from texts the students have read the previous year and uses them to create what it claims to be a superior and comprehensive view on the world and governing. Students then turn to selections from important writings from the Han dynasty such as the Shiji (Records of the Grand Historian).

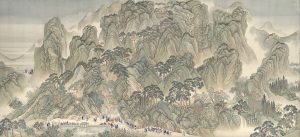

A selection of poetries is offered, including Six Dynasties poems by Tao Yuanming and the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove, as well as Tang dynasty verses by Wang Wei, Li Bai, Du Fu, Bai Zhuyi, Hanshan, and others. Essays by writers such as Han Yu and Ouyang Xiu are examined before the class turns to major Neo-Confucian thinkers of the Song and Ming dynasties, including Zhang Zai, Cheng Yi, Zhu Xi, Lu Xiangshan, and Wang Yangming. Students delve deeply into two chapters of the Liji—the Daxue (The Great Learning) and Zhongyong (Doctrine of the Mean)—which become canonized in the Song dynasty as two of the Four Books required for exam candidates (along with the Analects and Mencius).