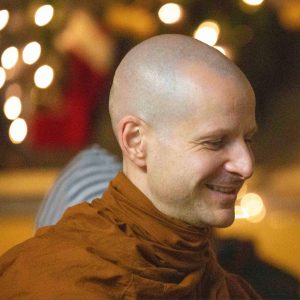

Explore Buddhist Wisdom: A Conversation with Ajahn Kovilo

Additional Q&A, Part I

During a recent online event with Thai Forest monk and DRBU alumnus Ajahn Kovilo, we received more thoughtful questions than time allowed the Ajahn to address. We sent these remaining questions to him, and he graciously took the time to provide detailed responses. His additional insights offer valuable perspectives on the Buddhist path and practice. The following is only the first part of Ajahn Kovilo’s responses; we will publish part two soon, so stay tuned.

Can you describe reincarnation/rebirth from a Theravada perspective?

There are different interpretations, but most people who look at the Theravada canon are focusing on the many, many instances in which the Buddha described rebirth as a multiple-life perspective. According to the suttas, before this life we had countless past lives, and in the future—unless we attain awakening in this life and thus put an end to samsara—we will be reborn. The Buddha teaches that this will continue happening until we attain enlightenment.

That said, there is a perspective from traditional Theravada Abhidhamma that very clearly describes how rebirth happens every moment. When we create a sense of “self” in this moment—by saying “I’m a good person” or “I’m a bad person,” or through any of the myriad ways we attach to identity—that impacts us and conditions our next moment in various ways. These ways can be wholesome or unwholesome, but this process perpetuates rebirth moment by moment regardless.

So there are those two perspectives, and many people who practice meditation in a Theravada way these days are actually allergic to the idea of rebirth meaning multiple lives. They feel like science has somehow overruled it, but the science is not conclusive yet. There is also definitely a traditional belief in reincarnation that is based on the fact that it’s virtually impossible to make a case that the historical Buddha didn’t believe and teach rebirth as a multi-life process. As for any individual practitioner, people can only believe what they believe, but it may be wise to have some openness to the idea if you find benefit in meditation and other aspects of Buddhism. Maybe put a question mark on one’s belief that there isn’t rebirth?

For those who don’t or can’t go on a retreat, are there day-to-day steps of practice that can guide individuals?

Most definitely. I won’t say this is more important than retreat, but it’s very important to ask ourselves, is my daily life practice, specifically when it comes to morality? I’ll actually mention two things here: morality and generosity.

Morality is also known as keeping the five precepts. In Theravada Buddhism, this is much less of a major life choice to make in some regards. One can commit to keep the five precepts today, right now, as soon as you read this. You don’t have to wait till next year’s ceremony; you can just take the five precepts at this moment. You can say, “I undertake the precept to refrain from killing, stealing, sexual misconduct, from lying, and from intoxicants.” And that’s huge. That can change a life immensely and for the better.

You can also simply find ways to be generous in everyday life. The Buddha in the Pali canon says, “If beings knew as I knew the value and worth of giving and sharing, they wouldn’t eat without having first given.” So, can you give something away before you yourself eat? It’s a good challenge. If there’s not another person you can give food to, can you give it to an animal? Feed some birds outside perhaps? Or maybe even put a little bit of food in the compost, feeding the beings present there?

Morality and giving. Challenge yourself.

What role does karma play in our suffering?

In Theravada Buddhism, the Buddha says, “What is karma? Karma is intention.” And the key insight of the Buddha is that our suffering comes about from unintelligent intentions. There’s a great essay by the modern scholar and monk Thanissaro Bhikkhu, and in it he says that the path to nibbana is paved with skillful intentions. Nibbana is the exact opposite of suffering in a certain way. Nibbana is the highest happiness. When one has attained nibbana, they have fully understood suffering, so it is no longer a problem for them.

What the four noble truths teach is that there is suffering in life, and that we cause it by our craving and our becoming energy. This is the karma that we create. So there’s karma which creates suffering. That’s the second noble truth. Then there’s the third noble truth, which is that there is an ending of suffering, ultimately nibbana. Every step along the way, though, we’re able to give up that craving a little, and this is also the third noble truth. The fourth noble truth is the karma of the path, the karma of non-suffering, the karma that will lead to the end of suffering.

What would you consider as the most impactful learning or experience you gained from DRBU that you would not have had otherwise?

Honestly, it was being exposed to very practiced Mahayana practitioners: Jin Chuan Shi, Jin Wei Shi, and the other monastics, as well as the very practiced lay people in the tradition, like Professor Douglas Powers and many of the teachers at DRBU, who have been practicing in the Master Hua-DRBA tradition for a long time. It gives me faith. Though I honestly have questions and doubts about the historicity of Mahayana sutras that I can’t quite get my mind around, I do have faith in these great teachers—the extremely sincere, devoted, peaceful people that are the teachers and monastics at DRBU, DRBA and CTTB.

Seeing them gave me faith in the practice of letting go. I was able to recognize that what most likely brought the most suffering for me at DRBU was not at all related to the coursework. Rather, it was my attachment to my own Theravada beliefs and to views regarding the weight of evidence for the historicity of the Pali canon versus the Chinese canon. Holding onto that in an inappropriate way just caused me suffering. Meanwhile, I could see these teachers who were talking about letting go, and I could see how the practice had influenced their life. It helped me realize that I don’t want to hold on so much.

Some may view Theravada as presenting itself as the most authentic preservation of the Buddhist teachings, with the Pali canon as the earliest and most reliable set of Buddhist scriptures…

Yes, most historians and Theravadans will agree with that. Certainly they believe it is the most historical, and many people would go further and say it is the most reliable as well. I believe in the historical argument for that.

But the question continues…

…Dogen, in the Shobogenzo Gyoji says, the true transmission is not a matter of words in scripture, but is ceaseless practice…

This is extremely true. You can read this in the Kalama Sutta—sometimes called the Kesaputta Sutta—where the Buddha said not to go by scriptural collection, nor by lineage, nor by reasoning or cognition, nor by popular opinion, nor by acceptance of a view after reflection, nor by the thought that because your teacher taught it, you must therefore believe it. Rather it advises that when you know for yourself that one thing is wholesome and another is unwholesome, then you should practice the path of the wholesome, especially when you see that this is the teaching of the wise. So I totally agree with Dogen’s statement there.

The question continues…

If the Buddha himself discouraged attachment to views…

Which he definitely did. This is one of the four attachments in Theravada Buddhism, along with attachment to sensuality, attachment to the doctrine and view of a self, and attachment to rights and rituals.

…does not the supposed Theravada claim to be the purest form of Buddhism connote a rigid attachment to view?

It definitely does, and it creates suffering. That’s why the Buddha suggested that we not hold onto views, even if a view is correct. Gravity is a well-established scientific principle, for example, but if one meets a kind person who just doesn’t believe in gravity, if one then causes oneself to suffer by holding on to egocentric attachment to the view that there is gravity, this is unwise. It just brings suffering.

Oftentimes such attachment—certainly when accompanied by righteous indignation—also weakens the strength of one’s argument for the truth of it. Definitely holding on to something that is pure, is impure in itself. That attachment is inherently impure.

Bhikkhu Analayo wrote an excellent book called Superiority Conceit in Buddhist Traditions, where he discusses four types of conceit found in modern Buddhism. The first is Theravada conceit. Specifically, Bhikkhu Analayo highlights the belief in the historical accuracy and “purity” of the Theravada tradition. He also describes Mahayana conceit: its practitioners often believe they are the great vehicle and have a higher view and purpose—that of helping others—which goes beyond the “selfish” Hinayana (“small vehicle”) view. The intention to help others is beautiful, but there are liabilities in holding this sort of view.

Bhikkhu Analayo also points to the male chauvinistic conceit, androcentric conceit, which you find in both the Mahayana and Pali canons. This is something that should definitely be thoroughly examined in oneself and in those suttas. The fourth type he describes is lay conceit. This is something you find in modern Buddhism, especially in the West. It is the view that lay practice is superior to monasticism because it’s egalitarian. Monastic practice is considered inherently conceited and antiquated—essentially just baggage from the East.

We should root out our conceit and attachments wherever we find them, because they cause us suffering, they’re not attractive, and for many other reasons that you’ll begin to notice once you start to practice. This is especially true when you have a somatic practice of noticing what attachment and clinging feel like in the body. You’ll come to find that you just don’t want to do that anymore. People who aren’t afflicted by attachment to views already understand this, and you start to see it for yourself as well when you pay attention. It’s just unbeautiful.

However, there is also a case to be made for holding onto correct views as part of following a path. A great simile for this is climbing a ladder. Just as when you’re climbing a ladder you don’t let go of the rung that you’re on until you have a firm grasp of the next ladder rung, similarly there is a place for holding onto the path. We hold to our precepts. We hold to our accurate perceptions of the world. But we don’t cling, and eventually we will let go.

The simile of the raft comes up here. We use the raft to get to the other shore. Then, we intelligently let go. We don’t burn the raft when we get to the other side. We don’t trash it. We don’t denigrate it. But we no longer carry it on our heads, because we’re on the other shore.

Keep an eye out for part two of Ajahn Kovilo’s responses, coming soon.